- Home

- Mary Schlegel

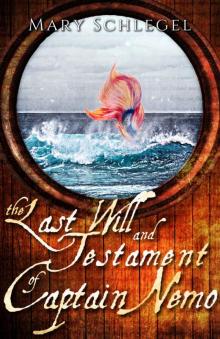

The Last Will and Testament of Captain Nemo

The Last Will and Testament of Captain Nemo Read online

The Last Will and Testament of Captain Nemo

To Mom,

for your unbridled enthusiasm about this project.

Author’s Note

This work of fiction is based heavily off of two classic works of literature: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne, and The Little Mermaid as written by Hans Christian Andersen. I have attempted to write it in such a way that anyone can enjoy it and follow the plot without any prior familiarity with either work (Hint: the Disney versions don’t count!), so I ask that readers who are familiar with the originals bear with me, as some of the information may seem a bit unnecessary or redundant.

Additionally, despite my efforts to make the story accessible to anyone and everyone, I do strongly recommend that to get the most out of the details of this story, readers take the time beforehand to familiarize themselves with the originals. The Little Mermaid is a crucial element in modern Western mythology, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, besides being a milestone in literary history and the development of the science fiction genre, is simply a joy and a phenomenal work in its own right.

Treat yourself to some classics…and enjoy The Last Will & Testament of Captain Nemo!

Kindest Regards,

Mary Schlegel, February 2017

12th of June, 1874

To Mr. Erwin Charles Harrison, Gulf of Manaar, Ceylon:

It is my sincere hope that this letter finds you well, for not a day has passed these thirty-four years of your life when I have not earnestly beseeched God for your well-being and happiness, such as is possible in this world of tyranny and injustice.

By such time as the messenger bearing this letter and the enclosed documents reaches you, I, the author, will have breathed my last and been laid to rest; an unfortunate incident of the 10th of June, 1874 has left me mortally wounded and so resolved to break my long silence towards you—a silence for which I hope you will, upon understanding the truth of the events that have driven my decisions and necessitated it, forgive me.

That this wound shall be my end, I am now certain; what remains uncertain is the length of life left to me, and so I shall, if you please, begin my account without further delay.

It is possible that you have read that hateful tale, “The Little Mermaid,” that was put to print a few years prior to your birth. To correct its vile, twisted account and complete the record of events as they unfolded is one of two purposes pressing upon my mind as I write to you.

It is imperative that you understand, first and foremost, the truth about the Mer people: They are neither a fancy concocted by the stupefied minds of drunken sailors, nor are they what that devil Mr. Anderson has termed a “fairy-tale.” They are a race as real and alive as that of the humans, and far superior in their ways as a society. Their pursuit and execution of justice are swifter and fiercer than any you will find amid the cesspool that is human law and government, and their sense of loyalty is rivaled only by the strongest and purest of human bonds.

If you have indeed (and I pray God you have not!) read Mr. Anderson’s butchery of the story, then you will have heard, of course, of “the prince.” This so-called prince was young Lord Timothy Rackliffe, the son of an Egyptian mother and a wealthy English nobleman who had left his ancestral home in Surrey in favor of the luxurious estate he had acquired in Egypt, on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Young Rackliffe reveled in the affluence at his disposal, spending countless days sailing one or another of his father’s many ships on the Mediterranean, and hosting his friends of both English and Egyptian nobility on board for lavish parties that often lasted for days.

It was on one of these voyages that Lord Rackliffe caught the eye of a young Mer girl—a princess of her people (a princess in truth, not merely a spoiled child of wealth granted royalty in name only by the liberalities of Mr. Anderson’s pen)—named Eyrál in her people’s tongue.

Fascinated by the lights and music of Lord Rackliffe’s parties on board his father’s ships, and drawn by his beauty (for that he was handsome of face cannot be denied, however black and dastardly his heart), Eyrál began a custom of following Rackliffe’s ships every time one of them ventured out upon the Mediterranean.

It was Rackliffe’s undeserved good fortune that Eyrál happened to be watching when one of his ships was dashed to pieces in a storm and sunk. The young man was unconscious, his body sinking far beneath the angry waves, when she snatched him from the depths and pulled him back to the surface. Would to God that she had let him drown! But no, I recant; for to do so would have been an aberration of her nature—she, whose heart held only selfless love, inestimable goodness, and boundless compassion!

Even when Eyrál had raised Rackliffe to the surface, the swells crashing over them threatened to drown him, forcing her to ensure his survival in the only way she could: by kissing him. It is a phenomenon as yet unexplained by scientific methods, that the kiss of one of the Mer renders its human recipient unable to perish by drowning; so it was in the unhappy affair of Lord Rackliffe’s rescue: Thus protected against the threat of asphyxia, the unworthy man remained unconscious but alive as Eyrál brought him to the nearest coast wherefrom she could see human habitations, that he might there be found and attended by his own kind.

It was a matter of some hours before the dawn broke and another human approached. During this interval Eyrál kept a constant vigil over the limp form of Timothy Rackliffe, still sprawled unknowingly upon the sand. As she watched, the kiss that had been granted of necessity to preserve his life did its cursed work on both parties, and Eyrál now discovered herself desperately in love with Lord Rackliffe.

Just as the sun rose, a human approached and Eyrál fled into the concealment of the water to see what would become of the scoundrel to whom her heart now belonged.

The approaching figure was a young girl, a resident of a nearby temple, who succeeded in rousing Lord Rackliffe and sought the aid of her sisters in the temple to pull him from the water and seek help for him.

Satisfied that he was safe and in capable hands, and fearful of being seen, Eyrál returned then to the ocean depths and to her people, but as time passed she found that she could not forget the man whose life she had saved, nor could she rid herself of the love for him that had rooted its poisonous tendrils in her heart. As time passed, her love only grew stronger, her yearning to be with Lord Rackliffe more powerful.

She followed his ships as before, once he had recovered sufficiently to return to his life of sailing and merry-making. She discovered the cove on which his father’s estate was situated and ventured close, even close enough to see him at his windows or on his balcony. Oh, that her love had been satisfied with wistful gazing, and had faded from existence! Alas, Fate was not so merciful as that.

So desperate did Eyrál become to see Lord Rackliffe and be with him again that she eventually sought the aid of a sea-witch, whom she begged for a spell that would transform her into human shape. The witch agreed and the spell was cast, with one stipulation: Eyrál must be loved by a human man—must be loved with a love strong enough that a human man desired to make her his wife. If she failed to win a human’s love, and the object of her affection, Lord Rackliffe, married another, the spell that granted her human form would turn on her and destroy her the sunrise after his wedding.

Notwithstanding such a fearsome condition, Eyrál readily agreed, her own passion for Lord Rackliffe having convinced her beyond all doubt that she could certainly win his love in return. The sea-witch gave her a potion to swallow once she reached land and, thus endowed, Eyrál abandoned her home and family without even a word of parting, knowing full well that they would attempt to diss

uade her from her quest.

Close by the Rackliffe estate was a stretch of beach where, Eyrál knew, the younger Lord Rackliffe was wont to go riding in the early mornings. It was to this place that she travelled, and waited until just before dawn to swallow the witch’s draught.

How the transformation took place, she never knew. Upon swallowing the draught she found her vision distorted, her ears pierced by a deafening ringing, and her senses scattered by an overwhelming dizziness. In this condition she lay on the sand, unknowing, until Lord Rackliffe did indeed happen upon her.

He saw her lying senseless, still half in the water, and drew the natural conclusion that she was the victim of a shipwreck, as he himself had so recently been. Upon discovering that she still lived, but being unable to rouse her, he lifted her in his arms and began carrying her back to his father’s house, utterly unaware that in his arms he bore the woman to whom he owed his life.

Into this situation, Eyrál awoke: borne in the arms of the man whom she had spent the last months loving from afar. And in that moment, her love for him grew deeper still, and she leaned her head on his shoulder and rested in her love and his nearness.

Lord Rackliffe, for his part, took Eyrál back to his father’s house and saw that she received the ministrations appropriate to the circumstance of a shipwrecked woman. His efforts to ascertain her name, as well as every other line of questioning or conversation, were met only with silence, for the Mer speak a language unique to them. Eyrál understood not a word that was spoken by Lord Rackliffe or any of his household, and dared not speak a word in her own tongue for fear of betraying her identity. Instead, she maintained an unbroken silence until those around her reached the consensus that she was a mute.

As she had in the way of worldly possessions only the sharkskin garment she had been wearing when she swallowed the witch’s draught, a wardrobe was provided for her. As she had never before possessed human legs or feet, she found walking both painful and difficult. This was easily explained in the minds of her hosts, who believed she simply needed time to convalesce. She mastered her newfound limbs quickly, however, and within a few days was walking well, though her feet remained tender and delicate.

Over the span of her convalescence, Lord Rackliffe grew fond of her as one would of a foundling dog, and treated her as one, but so hopelessly in love was she that she suffered all without complaint—even with gratitude! When he had her dressed as a pageboy so that no one would question her accompanying him on hunting trips, she complied with a naïve sweetness that only made his behavior more repulsive by comparison. When he placed a cushion on the floor outside the door to his private rooms for her to sleep on at night—as if she, a princess of the Mer and the savior of his very life, were truly nothing more than a favored dog!—she accepted all with gladness.

Her sweetness of temper and beauty of spirit made her a favorite among everyone in the Rackliffes’ household, from the Lord and Lady to the lowliest servant. However, if she believed that her perfect devotion and saintly submission to Lord Rackliffe’s unforgivable cruelty would win his love, she was sadly mistaken. While she slept on her cushion outside his door and accompanied him on his hunts and attended his lavish shipboard parties, his affections were being lost to another: the temple maiden who had discovered him on the beach where Eyrál had dragged him after the sinking of his ship.

A few months after Eyrál’s arrival, an announcement was made of the younger Lord Rackliffe’s engagement to that same temple girl, the daughter of a wealthy and influential Egyptian businessman. Arrangements for the wedding were made, a grand celebration aboard Lord Rackliffe’s finest ship was planned, and of course, Eyrál was invited.

The Mer princess knew full well that Lord Rackliffe’s impending marriage would mean her death, thanks to the sea-witch’s spell, and her heart broke at the realization that the man for whom she had sacrificed everything—for whom she was about to give her life!—shared nothing of her devotion. And yet so great was her love of him, and so good was her heart, even in the face of losing both love and life, that she held up her head, smiled upon Lord Rackliffe and his new bride, embraced them both to show her goodwill, and danced with more joy and abandon than any of the other guests at the celebration.

The wedding night came. The guests, weary from their revelry, retired to their cabins. Lord Rackliffe and his bride withdrew to the tent that had been erected for them in the middle of the ship. Only the night watchman and Eyrál still stirred.

As she stood at the bow of the ship, a cry came to her from the sea. Her sisters, distressed by her rash and vain pursuit of the prince, had themselves gone to the sea-witch to seek a counter-spell, one that would allow their sister to return to her life among the Mer. The witch had granted their boon in the form of a knife. If Eyrál were to use this knife to slay the prince before the approaching sunrise brought her death, her Mer form would return to her and she would be free to rejoin her sisters.

Pained by their mournful entreaties, Eyrál accepted the knife her sisters offered and stole into the tent where Lord Rackliffe and his bride blissfully slept in each other’s arms. But so great was her love, so good was her heart, that even in the face of her own destruction she could not take his life.

She returned to the bow of the ship and looked down to where her sisters eagerly waited. But to their dismay, she cast the knife from her and withdrew to the center of the ship, away from their sight so that she might not inflict upon them the pain of witnessing her end.

The sky colored, the sun rose, and yet Eyrál did not die as she had anticipated. No, indeed, for the witch’s spell had not required the love of Lord Rackliffe himself; it had only required the love of a human—and there was a human on board that ship who loved her with body, heart, and soul: myself.

I, in that former life, was Charles Alim Harrison, son of an English sailor and an Egyptian fisherman’s daughter, and a sailor on Lord Rackliffe’s vessel. Though as ignorant as anyone regarding her true identity, I had nonetheless fallen deeply in love with her angelic countenance and sweet, gentle disposition, and the treatment I had witnessed her receiving at Rackliffe’s hands kindled a fury in my breast that I could scarcely contain. Only the love for him that I saw in her eyes had thus far prevented me confessing my love and offering her my being in its entirety.

It so happened that I was the night watchman on duty, and from my vantage point I witnessed the exchange between Eyrál and her sisters. Though I was at that time unacquainted with their tongue and so could not decipher the details of what was being said between them, the idea of it all was clear. All my life I had heard legends, tavern tales, and rumors of the Mer people. Now I saw them before my very eyes, and with them the revelation that the woman whom I loved was one of them, transformed by unknown means into human shape!

I watched as Eyrál entered the tent, to see whether she would carry out the deed or not. God knows, I would have loved her even had she killed him, and would have been glad to see justice dealt to his cruelty! But, as I have previously stated in this record, such an action would have been contrary to the goodness and purity of her soul.

She reemerged from the tent and cast the knife into the sea, much to the evident dismay of her sisters, who, after rending the air with mournful wails, plunged beneath the ocean’s surface and were gone. Eyrál blew kisses after them and then withdrew to the center of the deck, seeming to await something.

So beautiful was she with her black hair gleaming in the growing light of dawn, her eyes as blue and full of tears as the ocean itself, even in her heartbreak, that at last I found my courage and dared to approach her. I knew that she would comprehend little, if any, of what I said, but that could not stop me from saying it.

I fell to my knees before her and confessed the ardor with which I loved her. If she failed to comprehend my words, she did not—she could not—fail to understand my meaning as I clasped her hand and pressed it to my lips. That she carried still a love for Lord Rackliffe in her heart, I kn

ew full well, and was content to let it linger a while yet, if she would only grant me a window of opportunity in which to prove my devotion and, with time, and if Fate kind, to supplant him in her esteem.

She watched and listened in silence as I laid bare my soul before her and begged for a chance to win her heart. That I was a wretch completely unworthy of her love, I could not begin to deny; my hope was in the fact that she loved Lord Rackliffe—my better in social standing, but nevertheless a scoundrel who had never deserved her affections. If such a blackguard as that had won her love, then perhaps even a lowly man such as I could aspire to do the same.

When I had pleaded my case I waited, still kneeling at her feet, to see whether I would be granted my boon, or rejected. What fearful anticipation filled me as she stared at me with widened eyes, making no movement to withdraw her hand from my grasp. What a thrill of hope rose within my breast as she brought her other hand to delicately brush her fingers against my face!

She searched my eyes with hers—and spoke!

“All…this time?”

Joy and relief flooded into my soul as the tide floods into a cove at that first hearing of her voice. Her words were halting, her sentence broken by the unfamiliarity of the English tongue, and yet no words have ever sounded so clear and beautiful to a man’s ears. In those three words she made me to know that she had understood my confession, she understood that I loved her.

“Yes,” I answered. “All this time.”

A tear fell from her eye, and yet she smiled. “How?” she asked.

“It does not matter,” I said, rising to my feet but still clasping her hand. “It matters only that I love you, and that I am yours, if you will have me. Come away! Let me take you from this place of sorrow and suffering. All that I have and all that I am are yours; if you can find it in your heart to accept that feeble offering, then let us go. Every breath in my body henceforth is dedicated to your happiness.”

The Last Will and Testament of Captain Nemo

The Last Will and Testament of Captain Nemo